Contenidos del artículo

- Immortel (ad vitam) (2004)

- Love (2011)

- Moon (2009)

- Repo men (2010)

- Never Let Me Go (Never Let Me Go, 2010)

- Under the Skin(2013)

- The Zero Theorem (The Zero Theorem, 2013)

- Gamer (2009)

- Mr. Nobody (2010)

- Cargo (2009)

- The Machine (2013)

- Eternal (Self/less, 2015)

- Coherence (2013)

- John Carter (2012)

- The Butterfly Effect (2004)

- The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009)

- Surrogates

- Brazil (1985)

- Donnie Darko (2001)

- The Darkest Hour (2011)

- Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010)

- Perfect Sense (2011)

- Vivarium (2019)

- Europa Report (2013)

- The Congress (2013)

- Annihilation (2018)

- Infiltrator (2001)

- Prospect (2018)

- Silent Running (1972)

- After Yang (2021)

This is an article that took me years to compile. It is as long, dense and endless as my experience with science fiction. Each time I edit it, I change my mind. It is quite possible that this list will grow over time, and in the end become my little legacy to my children. I spent many hours enjoying these movies. They made me who I am.

Without further ado, welcome to Avedon’s stellar catalog.

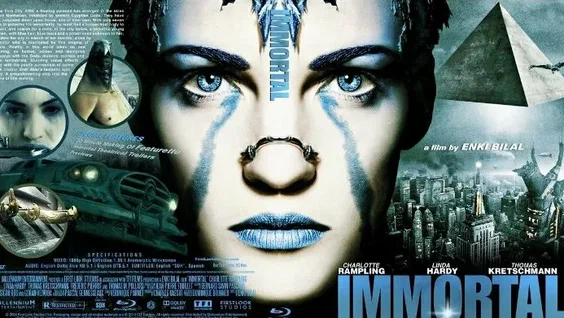

Immortel (ad vitam) (2004)

A pyramid suspended over Manhattan. Inside, the gods of Ancient Egypt judge Horus for having interfered with humans. He, condemned to death, is given a few more days to find a fertile body and father a divine child. That’s the premise. There is no other movie like it.

Directed by Enki Bilal, European comic legend, Immortel is a loose adaptation of his own work “The Nikopol Trilogy”. Bilal mixed real actors with CGI when Avatar didn’t exist yet, and the result is… weird. Not because it’s ugly, but because it’s cold, alienating. Everything seems about to break: the eyes, the gestures, the textures of the digital characters. And yet, therein lies its strength: the visual malaise accompanies the dystopia. It is not a failure, it is a statement of intent.

The story moves between the political and the mythical. Nikopol, a former dissident cryogenized by an authoritarian state, returns to a corporate world, mutated. Jill, the woman with whom Horus intends to reproduce, is an artificial being who barely knows what pain is. She will. Because Immortel is emotionally brutal when he wants to be. There is a scene – raw, uncomfortable – where the god possesses Nikopol and forces contact with Jill, who is not yet fully human. Consent is suspended in limbo between the biological and the symbolic. It is mythological morbidity, but also a reflection on the body as a battlefield.

Commercially it was a disaster. No one knew how to sell it. Its mix of primitive animation with adult themes, its slow pace and abstract script kept it out of the commercial theater circuit and major festivals. France did not know how to embrace it. Hollywood didn’t even look at it. But today, Immortel has remained a unique fossil: a science fiction film with gods, sex, biotechnology, political exile and existential cold.

It is not round. But it is unrepeatable. And that makes it, without a doubt, one of the best science fiction films I’ve ever seen.

Love (2011)

There are films that cost millions and leave you with nothing. And then there’s Love, which was shot with a Canon 5D camera, inside the garage of the director’s parents, with sets built by hand with recycled parts. The funny thing is that it doesn’t look like it. And the truly amazing thing is that, despite everything, it moves.

The story is minimalist: an astronaut sent to the International Space Station loses contact with Earth after a global catastrophe. Isolated, not knowing if anyone else is still alive, he begins to lose track of time, his identity and, in a way, his humanity. It all comes down to his mind, his loneliness, and an old diary of an American Civil War soldier he mysteriously finds on board. That diary becomes the last thread that connects him to the world.

What begins as a story of spatial isolation ends up as a meditation on memory, human connection and the ultimate meaning of existence. In the midst of that emptiness, the protagonist wonders not only what makes us human, but why we need others to remain so.

There’s a scene where he just looks at the Earth, floating silently, and says, “I don’t know if anyone’s still there. But if you’re listening to this…thank you.” Seldom has emptiness said so much.

Love was financed by Angels & Airwaves, the band of Tom DeLonge (yes, the one from Blink-182), who also signed the soundtrack. The experiment was a strange one: an indie sci-fi film as a visual extension of a concept album. At the box office, it went unnoticed. But that makes it even more valuable.

You won’t see Love on any list of the best sci-fi movies. That’s why it’s on this one.

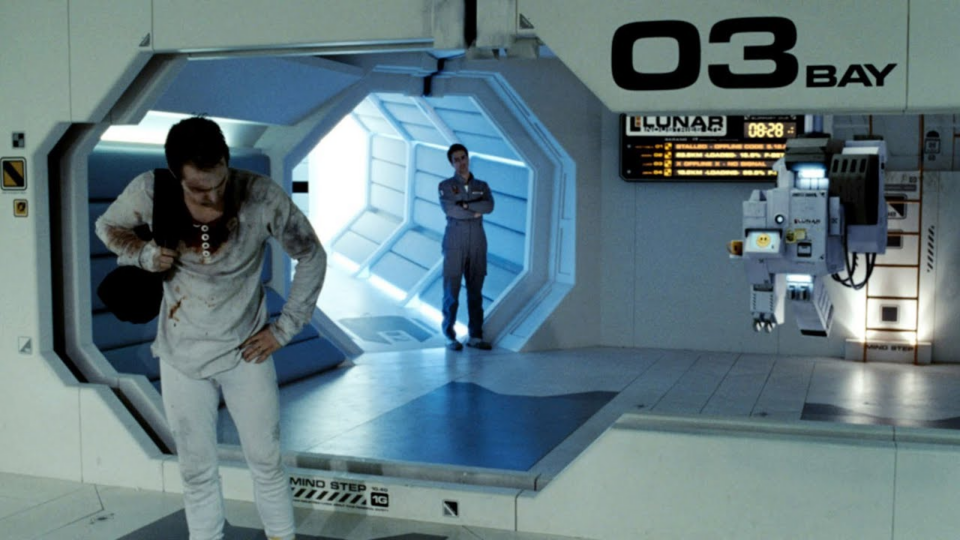

Moon (2009)

There is an ancient sadness floating in this film. It is not the sadness of heartbreak or death, but something grayer, more mineral: the sadness of discarding, of knowing that one is replaceable.

Moon, Duncan Jones’ debut feature, is one of those films that seems small, but sticks in you like a rusty needle. On the surface, it’s a science fiction story: Sam Bell works on a moon base collecting helium-3 for an Earth corporation. He’s been there for three years. Alone. He talks to an AI named GERTY – Kevin Spacey’s anesthetic voice – and clings to recorded messages from his wife like someone clinging to a memory before it’s erased.

But then Sam has an accident. And when he wakes up… there’s another Sam.

What follows is a painful unfolding about identity and obsolescence. Moonbase is nothing more than a conveyor belt of souls: each Sam thinks he’s unique, but they’re all recycled versions, tossed into the landfill when they start to break down inside. There are clones. There are business ethics turned exploitative system. But above all there is humanity trapped in silence, in the white fog of the moon, in the certainty that there is no return.

Rockwell is immense. He is the exhausted man, the one who laughs for not crying, the one who bleeds without epic. His every gesture reveals an inner world that crumbles without a sound.

Moon premiered without making much noise. It went through Sundance, swept Sitges, and was still ignored by the general public. Maybe because it has no spectacle, no monsters, no hope. It only has truth. And truth, in science fiction, is usually more uncomfortable than aliens.

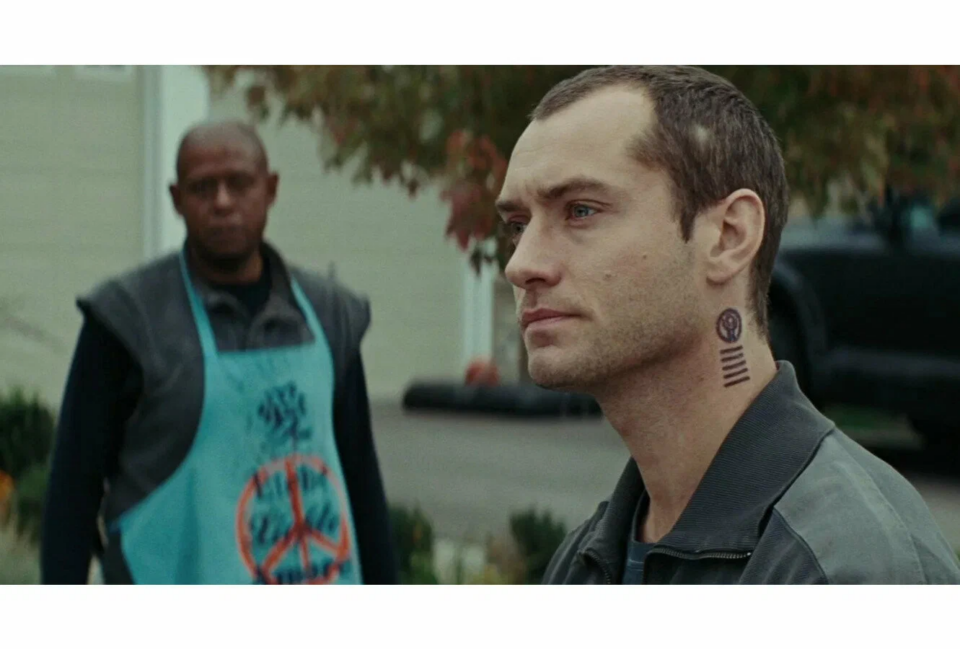

Repo men (2010)

At some point, someone decided that bodies were divisible property. That you could sell the liver, the pancreas, a spare pair of lungs, with flexible financing. And the worst thing is not that they did it, but that it worked. Nobody rebelled. We all happily signed a contract that said living was a renewable subscription. One more fee. Like Netflix, but with blood.

In that world, Remy is what comes next: the tax collector. Not of taxes, but of organs. He goes house to house – knife, briefcase, anesthesia optional – and recovers parts for the company. There is no hatred, no guilt, only efficiency. He does it like someone repairing a broken appliance. Until, of course, something breaks inside and he can no longer pretend that this was work, and not a surgical procedure.

The breaking point is not when you have an accident. It’s not when you wake up with a mechanical heart beating in your chest like an hourglass counting down. It is before. It’s when he begins to dream of what he can no longer give back. When he finds himself on the other side of the scalpel, and realizes it was all a lie. That he was never in control. That humanity is for rent, and it’s always due.

There is a scene where he and a woman, also marked by debt, operate on each other to remove the devices that give them away. Not in an operating room. In a kitchen. No gloves, no light, with absurd music in the background that turns the grotesque into an intimate act. Almost tender. As if, within the pain, there was still something similar to love.

I don’t know why this movie didn’t work. It has pace, it has action, it has familiar names. But maybe it was too explicit in what others disguise as spectacle. Maybe no one wanted to see that the only thing standing between you and death… is a bill. And that there is no science fiction more real than that.

Never Let Me Go (Never Let Me Go, 2010)

Some futures need no machines, no wars, no distant stars. All it takes is a slight adjustment in history. In Never Leave Me, that adjustment is simple: science has found a way to prolong the lives of normal people. What no one says is at what cost. Or rather… whose price.

The main characters – Kathy, Tommy, Ruth – grow up in an English boarding school, among woods, art classes and silent walks. Everything seems normal, but something doesn’t fit. There is an artificial calm, as if life were written in pencil, about to be erased. Little by little the truth is revealed: they are clones. They were created to donate their organs. They will not have children. They will not travel. They will not age. They will only wait their turn to be emptied little by little, until they are completely empty.

The most devastating thing is that they accept it. They never rebel. There is no revolution. Science fiction here is not a dystopian cry, but an elegy. Because the tragedy is not in what happens, but in the way they assume it. With dignity. With tenderness. As if they knew no other way to live. As if love, friendship, jealousy or beauty were only postcards of a world to which they would never fully belong.

I saw this movie one gray afternoon. I had already read Ishiguro’s book, but that didn’t stop it from hurting as if I didn’t know what was going to happen. There are scenes where hardly anything happens, and yet it hurts. An awkward gesture from Tommy. A look from Kathy as she watches the sea. That way of loving with her hands tied, as if she knows that what little she has will soon be taken away.

There are no monsters. No villains. Just a perfectly polite system that decides who lives and who serves as a spare. It’s one of the best sci-fi movies, though many will say it’s not even that. But it is. The science is already there, and the question is not whether we could do it, but whether we would have the courage not to.

Under the Skin(2013)

Scarlett Johansson plays something that has no name, no clear purpose. A female form that drives a van through Scotland and picks up lonely, unsuspecting men. Normal, even real men -because many were, filmed with hidden camera-. And one by one she takes them to a place we don’t understand. A black space, perfect, where they walk towards it as if hypnotized and then sink, naked, in a kind of thick liquid. No one screams. Nobody asks for help. Everything sinks in silence.

I wrote a specific article about this movie, where I said that it is not a movie about aliens, but about the alienness of our own flesh. And I still believe that. She doesn’t kill them, not at first. She just looks at them. She examines them. She undresses them without violence, as if she doesn’t yet understand what we are. And maybe that’s the most disturbing thing: that the monster doesn’t hate, it just doesn’t understand.

But then he begins to understand. To notice her body, her limits, her skin. One scene, almost trivial, shows her looking at her own hands with attention. Another, more brutal, confronts her with sex for the first time, and she discovers that her human envelope has doors she doesn’t know how to use. And then, something cracks. She can no longer look at humans the way she used to. Something has been contaminated. She is no longer quite them, but she is not quite her either.

There is pain in that. And also beauty. An uncomfortable, aseptic, cold beauty. Like an empty operating room illuminated by Mica Levi’s music: hypnotic, nervous, almost animalistic.

Under the Skin doesn’t want you to understand anything. It just wants you to feel the ice on the back of your neck, the slow vertigo of watching someone who looks like us trying to figure out if it’s worth being human. Maybe it’s not. Maybe he knew too late.

I don’t remember exactly what I did when it was over. I only know that I didn’t turn off the screen right away. I just stood there, with the screen black, waiting for something that wasn’t coming. As if there was still someone watching me from inside.

The Zero Theorem (The Zero Theorem, 2013)

Qohen Leth works from an empty church in a tight black suit like an insect. He shaves his head, talks about himself in the plural and waits for a call that never comes. He has to prove an equation: that everything, literally everything, tends to zero. There is nothing else. That is his task.

The assignment comes from a mega-corporation that doesn’t explain anything. They send you colorful interfaces, stupid algorithms, eccentric supervisors. They assign him a digital prostitute to keep him from collapsing. A child genius to keep him from thinking too much. And they keep an undisguised eye on him, because surveillance is no longer a threat: it is part of the emotional salary.

Everything in Teorema Zero is overloaded, unhinged, garish. As if the future were designed by caffeine-addicted advertisers. The screens are like insects. Windows don’t open. Food is bought by catalog. Colors don’t soothe, they push. People dance alone in empty rooms. Everyone smiles too much. Nobody says what they think.

Gilliam doesn’t build a world, he overflows it. He crams ideas in as if they were misplaced furniture in a small house. Religion as failed architecture. Sex as faulty software. Work as self-inflicted punishment. Inner life as background noise. Sometimes the film collapses from excess. At other times, through exhaustion. But something remains. Something remains in the margins, where films that err by excess still breathe.

Waltz plays Qohen as a being without affective language. He seems neither human nor machine, but one of those people who have worked so hard at silencing themselves that they no longer remember how to sound. When he falls in love, he doesn’t celebrate: he panics. When someone touches him, he withdraws. When asked what he wants, he answers that he wants to work from home. Not for convenience, but because that way, if the phone rings, she can pick it up on time.

Halfway through the film one begins to wonder if the call exists. Or if it is just the name given to that silence that comes from far away. It doesn’t matter. The call doesn’t matter. What matters is to keep processing absurd lines of code while life disintegrates behind the screen. Just in case.

Gamer (2009)

People see Gamer and think it’s just noise. Explosions, boobs, epileptic montage and Gerard Butler screaming through gritted teeth. And yes, it’s all that. But it’s also something else. A pre-Black Mirror dystopia, shot as if Tony Scott had choked on Call of Duty and a bottle of Jäger. Science fiction shot with the stomach, not the brain. That’s why it works.

The premise is one of those that seem exaggerated and yet are just a step away from becoming documentary: in the near future, video games have evolved to allow real players to control real people. People who allow themselves to be managed, in exchange for money. Some do it out of necessity. Others because they no longer know how to move on their own.

There are two main games: a combat game – an FPS called Slayers where death row convicts are turned into human puppets for mass entertainment – and a sex game -Society, a grotesque cross between The Sims and Pornhub-, where tuned and empty bodies are controlled by users who are obese, drunk or just desperate to feel something. Anything.

Gerard Butler plays one such prisoner. He is about to survive the games necessary to win freedom. But of course, the system is not designed to release anyone.

Everything in Gamer is unpleasant: the light, the rhythm, the sound, the characters. There are no heroes. There are functional bodies, interface errors, spit, dirt. The camera doesn’t linger on anything, as if it too is drugged. But in the midst of all that chaos, there are moments that cut. Like when we see the player controlling Butler: a rich kid, surrounded by screens, eating fried chicken while commanding a real man to kill or be killed. And he smiles. Not because he’s cruel. But because he feels nothing.

Gamer was despised at the time. Too loud to be taken seriously, too clever to be just a blockbuster. But there it is, standing the test of time better than many “respectable” films. Because it smelled something that was already in the air: flesh as avatar, identity as interface, spectacle as prison. It just shouted it out too soon.

Mr. Nobody (2010)

There are decisions that sometimes seem small. Turn left. Saying yes. Not answering a message. At Mr. Nobody Each of these decisions opens up an entire universe. Or several. Jared Leto plays a man who remembers all the lives he could have lived. Not one, all of them. Not as nostalgia, but as a burden. Like a puzzle without a center.

History does not go in a straight line. It spirals, or branches, as if someone had taken all the possible biographies of a single man and assembled them in parallel. In one, he marries a woman he doesn’t love. In another, the woman leaves him. In another, he finds her. In another, he dies a child. In another, he is not born. None of them is definitive. All are valid.

I saw this movie one early morning, after an absurd discussion that left me sleepless. It was winter, and in the street there were only street lamps and badly parked cars. I didn’t understand everything that was happening on screen, but something stayed with me: the feeling that living is not about moving forward, but about leaving versions of oneself behind.

Visually it is beautiful. Each timeline has its aesthetics, its color, its emotional climate. There is science fiction, yes: space travel, immortality, interviews in the year 2092. But that’s the wrapping. What lies beneath is pure fear. Fear of choosing. Fear of being wrong. Fear of getting it right and staying there, trapped.

The dialogue is sometimes too literary. The ideas, too big to fit in a single film. But it doesn’t matter. Because it’s not about understanding. It’s about looking at the character and seeing your reflection in all its versions, even the ones you never dared to be.

Cargo (2009)

Space, as Hollywood usually imagines it, is full of noise. Alarms, engines roaring, explosions, heroic speeches. But Cargo comes from somewhere else. She’s Swiss – not Swedish, Swiss – and that background changes everything. There is no epic here, no square-jawed heroes. Just tired bodies floating in machinery they barely understand, performing repetitive functions in rusty ships. It’s gray, functional, hopeless science fiction. And that’s why it works.

Earth is doomed. Overpopulation, ecological collapse, overcrowding in orbital stations. There is only one way out: emigrate to Rhea, a supposed Eden under construction. But no one has been there. No one to return. Rhea exists only as an advertising promise, like the sign of a resort that no one has ever set foot in.

Laura, a burned-out doctor, joins the crew of a cargo ship to earn points and buy her passage. The ship departs with six crew members, all asleep in cryosleep pods. One must stay awake in shifts to watch the route. When her turn comes, Laura begins to hear noises. Footsteps. Thumps. Bodies that shouldn’t be moving. Something, or someone, moving through the empty corridors.

So far it sounds like a space thriller. But Cargo is something else. There are no aliens. There are no scares. What there is is distrust, confinement, rusty surveillance cameras, and a growing suspicion: what exactly are we transporting? What exactly are we willing to ignore in order to reach a better future?

As the mystery unfolds, the seams of the entire system begin to come out. The missions, the falsified records, the severed transmissions. We discover that Rhea may not be what she seems. And that the ship, in its slow, crooked silence, is more alive than any of its occupants.

Visually it has nothing to envy to the big ones. Cargo gets by with few practical effects, dirty lighting, analog technology and a production design that looks like something out of a Soviet nightmare. Every shot is functional, ponderous. Every door seems to close forever.

It is not a perfect film. The pace is leisurely, sometimes too much so. But if you’re looking for serious, atmospheric, European sci-fi with a mystery that simmers without being rushed, there’s something special here. Very few have seen it. But those who have, don’t get rid of it easily.

The Machine (2013)

At first it seems like just another one: artificial intelligence, cyborg soldiers, unscrupulous government, guilt-ridden scientists. But The Machine gradually goes off the rails. Not out of brilliance, but out of sensibility. It’s low-budget sci-fi with the emotional ambition of something bigger, as if it wants to masquerade as a thriller but comes off as a tragedy.

A military researcher – Callum – works in a secret base where they develop neural implants to repair wounded soldiers. The project progresses slowly until Ava appears, a brilliant scientist with her own ideas and a porcelain face. Between them there is respect, shared intelligence, something that could have been a love story if things didn’t go wrong so quickly. Because, of course, they do.

Ava dies, and her face, her speech patterns, the way she looks, are used to build an artificial intelligence. A replica. But The Machine does not stop there. The AI does not want to conquer the world. It does not want to obey blindly. It just wants to understand what it is to be human. It walks barefoot. It listens to music. It asks questions of no apparent importance. And that detail, that childish gesture, is what makes everything more uncomfortable. Because she is not a monster. She is an innocent creature trapped in a violent system.

There is one scene that sums it all up. The AI discovers it has no sex organs. It says it without drama. It only notes a limit. And in its own way, it regrets it. Not because it wants to “use” its body, but because it senses that something important was denied to it. Something that defines who we are without us being able to fully explain it.

The film never fully explodes. The script has holes, the pacing deflates in stretches, and some subplots lead to nothing. But that doesn’t matter so much. The Machine doesn’t enter through the head. It enters through that hole left by what could have been. An amputated love story. An idea that didn’t develop. A half-hearted humanity.

It is not a masterpiece. But there is something honest in how it treats its creature. Something almost tender, as if the only thing he wants to tell us is that, if someday we build artificial life, maybe we should not teach it to serve, nor to fight, nor to obey. Maybe the first thing should be to teach it to be alone without breaking.

The parallels withBrin’s Black Tears, my second novel, are there.

Eternal (Self/less, 2015)

A millionaire man is dying. Not dramatically, but slowly, clinically, well cared for. He has power, he has influence, but his body is wasting away just like everyone else’s. So he pays for an experimental procedure: transfer his consciousness to a young body. Not cloned. A real one. Donated. Or so he is told.

From there, Eternal moves between thriller and science fiction like someone walking a tightrope. It is not an elegant film. Sometimes it steps on it. At times it screams more than it should. But in the midst of its commercial awkwardness there is an idea that keeps scratching: what is left of you when you occupy another body? What is “me” when the memories are not yours, but the pain is?

Ryan Reynolds plays a new host. A body that begins to reject the occupant. Not with allergies or rashes, but with foreign memories, nightmares, scenes that he does not recognize but feels as his own. Because that body was not empty. It had a history. A daughter. A life torn away.

I saw this film one afternoon without expectations, wanting not to think too much. But when I finished I got caught in an image: the protagonist looking at his reflection, not with amazement, but with suspicion. As if I was beginning to understand that immortality was not living forever, but never being able to return.

Eternal is not complex. It is not risky. But it has something dirty, uncomfortable, that keeps it away from hygienic science fiction movies. No one is completely spared here. Neither the one who sells the technology, nor the one who buys it, nor the one who suffers it from the inside.

And while it’s all wrapped up in a layer of action movie so as not to scare the average viewer, the core is there: death as business. Conscience as currency. Identity as luxury.

The concept of eternal life is a very cyberpunk concept that started with the Neuromancer trilogy. Many have exploited it, but this film focuses on it in a special way.

Coherence (2013)

Eight people get together for dinner. Wine, jokes, old tensions. Nothing special. Outside a comet passes by. Nobody gives it any importance. Then the light goes out. And when it comes back… they are no longer in the same reality.

That’s all. And that’s enough.

Coherence was shot in five nights, without a closed script, with the actors improvising from loose cues. The house is real. So are the conversations. At first nothing happens. But details start to arrive that don’t fit. A broken cell phone that is no longer broken. An envelope with photos that no one remembers taking. An identical house, across the street, with the same people having dinner… but not quite the same.

There are no visual effects. No flashbacks or marked timelines. Just growing confusion. Fear arrives as things you don’t understand arrive: slow, cold, inevitable. One of the characters unwittingly says it, “If there are infinite realities, why not choose the one that suits you?” And what starts as a quantum curiosity turns into emotional carnage. Because to choose is also to give up. And when every version of you wants to survive, the question is not who you are… but how many versions of you you are willing to betray.

I saw this movie one night with friends, after dinner, and I swear it took minutes for us to talk to each other normally again. Not because anything weird was going on. Because we were no longer sure who had said what. As if the words had been duplicated without permission.

Coherence is not just a great science fiction movie. It is a trap. A small box that when you open it releases all your insecurities, your decisions, your contradictions. It’s so simple that it’s scary. And that’s why you don’t forget it.

John Carter (2012)

Sometimes a movie doesn’t come at the right time. Not for the world, but for you. I saw John Carter one silly afternoon, the kind where you don’t know whether to go outside or hide under a blanket. I wasn’t expecting anything. And yet, I was glued to the screen as if someone had opened a forgotten door for me when I was twelve years old.

The story is absurd and beautiful. A sad man, tired of his world, ends up in another world where everything has a different density. On Mars. But not the Mars of maps or space missions. This Mars is dry, golden, populated by impossible creatures and ruined cities still waiting for someone to save them.

And he jumps. That obsessed me: he jumps. He doesn’t walk, he doesn’t run. He jumps as if the weight of his former life has been suddenly lifted off. Not because he is a hero. Because he has nothing left to lose. And in that jump – clumsy, long, almost ridiculous – there is something more powerful than any epic speech: the gesture of someone who finds, at last, a place where his body does not hurt so much.

The film does not pretend to be profound, and that makes it more honest. It indulges in the naive, the outdated, what today is considered cheesy. And that, in these times of CGI-decorated cynicism, is a small miracle.

I don’t remember how it ends. Nor do I need to. I remember the red sand, the wind, a man lost between worlds who, at last, decides to stay.

The Butterfly Effect (2004)

There are decisions you don’t make, yet they haunt you. Tiny moments. Things you said. Things you didn’t say. A letter you didn’t send. A door you didn’t open. The butterfly effect latches on to that: the possibility of going back to those instants and correcting them. But each correction opens a new wound.

The protagonist discovers that, by reading his childhood diaries, he can mentally return to those moments. Not with nostalgia, but with real presence. He can rewrite what happened. And of course, he does. Over and over again. He does it out of love, out of guilt, out of fear. But the more he tries, the more the world he’s trying to save breaks down.

It is not an elegant film. It’s clumsy at times, awkward, even somewhat melodramatic. But that makes it more relatable. Because there is something desperate in that character, and in his look. He wants to fix everything without knowing that to fix something is, many times, to break something else. Changing the past doesn’t give her peace. It only changes the questions.

I saw this movie at a time when I was also going over my own mistakes with the false idea that, if I had done this or that, everything would be fine now. But no. Because what one seeks in going back is not to change the facts. It is to save someone. And that is almost never possible.

The Butterfly Effect is not hard science fiction. It’s emotional, juvenile, dirty, and it’s not ashamed of that. What it proposes is not a time travel system, it is an autopsy of what can no longer be touched. And for that, it still hurts.

The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009)

There are loves that are built with time. This one is built with its absence.

He disappears. That’s how it all begins. Not when they meet, not when they fall in love. But when she begins to understand that loving him means accepting his constant disappearance. Not out of fear, not out of abandonment. Because of a genetic malformation that makes him jump in time without warning. Like a cosmic tic. Like an apology that is always late.

He appears in her childhood, then in her adolescence, then in her adulthood, as if it were a series of visits that life grants her before taking its toll. She learns to live with his comings and goings. She learns to weave memories without knowing if tomorrow he will remember the same. She learns to sustain a life alone while he continues to fall through the holes in the calendar.

It is not a science fiction story, even though there is time travel. It is a story of waiting. Of having to love in delay. Of learning that, when you love someone who can’t stay, the only thing you can do is stay.

It didn’t mark me because of its dialogues or its ending. It marked me because I understood -without anyone saying it- that time is not measured in days, nor in clocks. It is measured in presence. In how many minutes of truth you shared with someone before the world -or whatever it was- took them away from you.

Beyond Time doesn’t need much more than that. And if it catches you at a time in your life where someone important is gone – even if they haven’t jumped in time, even if they’ve just left – then something touches you. And it doesn’t go away.

Surrogates

Everyone is young, attractive and moves like their back never hurts. But it’s a lie. Behind every perfect face is someone locked up at home, lying in a capsule, living through an avatar. A surrogate. An enhanced body that goes out into the world for you while you wither away without moving. Without exposing yourself. Without risking yourself.

Surrogates states that as a fact. No one is arguing whether it’s right or wrong. It is what it is. A logical evolution. Total safety, uniform beauty, zero friction. All equal. All alone.

The protagonist begins to suspect something is wrong when someone kills a surrogate… and its user as well. Something doesn’t add up. Technology is no longer infallible. Or maybe it never was. Yes, if you’ve read Brin’s Black Tears, you’ll find another clear reference here.

The film is disguised as a thriller, with police investigation, chases, conspiracies. But what remains is something else. A question that creeps underneath the whole plot: when was the last time you really touched someone? When was the last time you showed your face without filter, without improvement, without fear?

I don’t remember what I thought of the ending. I don’t think it doesn’t matter anymore. What I am left with is that image: that of real bodies, pale, immobile, moving at a distance a version of themselves that no longer has anything to do with who they were. And in between, the suspicion that perhaps, in part, we already live like that.

Brazil (1985)

Everything is in order. Papers are filed. Machines spit out forms. Information flows in tubes, in wires, on screens that no one quite understands. Everything works. And yet, something smells rotten. Not by rebellion. Out of routine.

Brazil is what remains when a dystopia ceases to be violent and becomes an administration. There is no explicit totalitarianism here. There are printers, cubicles, automatic coffee machines, badly registered torture bills. Evil does not scream. It is processed.

The protagonist, Sam Lowry, is a gray guy who just wants to be left alone. He works for the system. He moves awkwardly within that tangle of rules and permits. But he has dreams. He dreams that he flies, that he escapes, that he loves. And that is enough to make him a suspect.

I saw Brazil with the feeling that someone had put my life in a distorted mirror. Not because I live in a dystopia, but because I know what it’s like to get lost among paperwork, poorly lit corridors, orders that no one signs but everyone complies with. That anguish of not knowing if what you do is right, only that it is what you do.

The film gradually unravels. It begins with a structure, a world, a logic. And it ends as many nightmares end: with no center, no exit, no certainty. Just a chair, a ceiling, an old song, and a mind that breaks into silence.

There is no redemption. There is no revolution. Just the hysterical laughter of a system that doesn’t need to punish you, because it has already absorbed you completely. I think this movie transformed me into the sci-fi fan I will always be.

A happy kingdom is my dark homage to the bureaucratic future, where decisions are automated and emotions are commodified. If Brazil made an impact on you, don’t miss it.

Donnie Darko (2001)

There are films that seem to be written from a lucid nightmare. It doesn’t matter if it all makes sense. It matters how it feels. Donnie Darko doesn’t ask for logic. It asks you to sit with it in the dark and not look away.

Donnie is a teenager who talks to a guy dressed as a giant rabbit. He tells him the world is going to end. And maybe it is. But it’s really him that’s falling apart. Or everything around him. The school, his family, his girlfriend, his brain. Everything vibrates like a reality about to collapse.

The film mixes time travel, tangent universes, planes falling from the sky, impossible theories, but that’s not what hurts. What hurts is the feeling that Donnie is alone. That he knows things no one else sees. That he is doomed to understand too soon what others pretend to ignore.

There are scenes that seem to be taken from an intimate diary written in the middle of a thunderstorm. A classroom conversation about Smurfs. A talk with his therapist about death. A bicycle. A letter that is never delivered. And music. Always that music. As if someone had found the exact tone between melancholy and threat.

I don’t know if Donnie Darko is a brilliant film or a beautiful accident. Sometimes it seems profound. Sometimes it’s just lost. But that’s its truth. That of many. That sense that there is an order behind things, even if you can’t see it. And that sometimes the only way to save others… is to erase yourself.

The Darkest Hour (2011)

First people disappear. They disintegrate. Just like that, without screams, without blood, without glory. One second they are there, the next they are gone. Something has erased them. As if someone had pulled the plug.

The aliens in The Darkest Hour have no form. They are electricity. Vibration. Invisible movement. And that, far from being a technical limitation, makes them more disturbing. They are not seen. They can only be sensed when it is too late. Like fear. Like a disease that you don’t know when it started.

The film takes place in Moscow. And that already makes it strange. The empty streets, the signs in Cyrillic, the gray architecture. Everything has a colder, more distant tone. As if the apocalypse were happening far from Hollywood, without dazzling effects, without heroes with prepared speeches. Just survivors without a plan, running between abandoned buildings while the world shuts down in silence.

The most curious thing is that there are no big action scenes. What remains is the hollowness. The empty city. The failing lights. The constant suspicion that there is nothing left to do, and yet we keep walking. As if something in us resists accepting extinction.

The Darkest Hour is not brilliant. It doesn’t pretend to be. But it has something that makes it stay. Maybe it’s that way of showing the end of the world without pride, without tragedy, without epic. Just a group of people with no answers, hiding from something they don’t understand, waiting for it to pass. Even though we all know it’s not going to happen.

Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010)

More than a film, it looks like a videotape forgotten in the back of a laboratory. A psychedelic trauma capsule from the eighties, played slowly, with dirty tape, melted edges, and music that you don’t know if it’s soundtrack or interference.

Beyond the Black Rainbow doesn’t want to tell a story. It wants to trap you in a windowless room with red lights, heavy breathing and a patient who never speaks. It all takes place inside an institution. Or a mind. Or of an experiment. It’s not made clear. There is a doctor. There is a young woman with psychic powers. There are corridors that look like the dreams of someone who has only slept under sedation.

The film progresses like a badly handled hypnosis. With slow, impossible shots, designed more to create discomfort than tension. There is no rush, no intention to please. Each image is constructed like a postcard out of a techno-esoteric nightmare: expressionless faces, silent rooms, neon, silence, neon.

It’s not for everyone. I don’t even know if it’s for anyone. But I saw the whole thing. Without moving. Without understanding why I didn’t get up. Maybe because deep down, her way of not explaining anything, of not giving comfort, was familiar to me. As if it had been there before. In some dead-end dream. At a time when everything was about to collapse, but nothing had happened yet.

Perfect Sense (2011)

First people start crying without knowing why. A thick, overflowing cry, which is imposed for no reason. Then, as if the body needed to be emptied of something, people lose their sense of smell. Not one at a time, not in isolation. The whole world. At the same time.

From then on, the senses begin to shut down, as if the human body were a nervous system that someone was switching off in phases. Each loss is preceded by an extreme emotional peak: euphoria, anger, sadness. An outbreak. And then, silence. One organ less. The world minus the world.

Perfect Sense does not try to explain what happens. There are no experts solving the mystery, no governments making decisions. Just people improvising how to live when you can no longer smell a city, taste a meal, or hear a voice. And in the midst of it all, two people meet. She studies the epidemic. He is a chef. His world – the world of taste, the world of excess – is the first to collapse.

The film does not show the disaster from the outside. There are no running masses, no burning cities. Everything is intimate. Apartments, beds, spoons. What hurts is not what is lost, but how we come to terms with it. Without struggle. With resignation. As if we were prepared to function without senses, but not without the company of another body next to us.

There aren’t many movies that treat the apocalypse as something that happens between two people brushing their teeth. This one does. Noiselessly. No need to justify anything.

Vivarium (2019)

They are going to see a house. Nothing more. A quick visit. A young couple, still with a future, still with options, enters an empty, clean, absurd housing development. All the houses are the same. The lawns are identical. The sky does not change. The salesman disappears.

They try to get out. They turn. They turn. They turn. They return to the same point. Everything is duplicated, mirrored, endless. Like a trap that has no doors, because it never needed them.

The next day, they are left a box with a baby. “Raise the child and you will be released.” There are no further instructions. The child does not cry. It does not smile. It screams. It imitates. It grows too fast. It speaks in a voice that doesn’t sound human. And everything they do – eating, sleeping, arguing, giving up – happens inside that house they didn’t want to buy. In a world that repeats itself like a model built by someone who doesn’t understand what it is to live.

Vivarium does not explain anything. It just pushes. It’s suffocating science fiction disguised as a suburban nightmare. And it works because it doesn’t exaggerate. Because what it shows – the routine, the confinement, the artificial cycle of being born, raising, dying – was already there. It just isolates it. He repeats it. He films it without windows.

There is a point at which you understand that the enemy is not the child, nor the invisible architects who have locked them up. It will leave you with a bitter taste, sorry.

Europa Report (2013)

A private mission travels to Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons, to search for life beneath its icy surface. There is liquid water. There is thermal activity. There are signs that suggest something might be there. It’s not a military expedition or a rescue trip. It’s pure science. Exploration. Data. Risk.

The film is constructed as a mockumentary. Fragmented images from security cameras, diary recordings, interviews after the fact. We know from the beginning that something went wrong. What we don’t know is what, or when, or who tells it from the truth and who from the reconstruction.

The spacecraft is small, functional, without decoration. The astronauts are professionals. There are no heroes. There are decisions. Protocols. Doubts. Communication failures. One dies on a spacewalk while trying to fix a broken system. Another disappears under the ice. The tension comes not from what is seen, but from what is sensed. There is something out there. Something that doesn’t respond. Something that won’t run away.

Europa Report is not looking for spectacle. It seeks authenticity. If extraterrestrial life exists, it’s not going to appear with lights and trumpets. It’s going to be a flash underwater. A background noise. A decision no one is prepared to make, but someone has to make it anyway.

The film does not speculate, it simulates. And in that simulation, in that contained coldness, it achieves something that many other more ambitious science fiction films fail to do: to show the real fear of looking into the abyss and receiving an answer.

The Congress (2013)

She accepts.

Not for ambition, not for money. For exhaustion. For that kind of tiredness that can no longer be cured by sleeping. Let them scan her. Every gesture. Every micro-expression. Her fear, her smile, her hesitation. They digitize everything. In return, they promise her never to have to perform again. They don’t let him either.

Years go by. The world bends towards another form of consumption. There are no more actors. Only licensed images, reproduced in infinite combinations. Versions of versions, adapted to each viewer. Robin Wright -or what’s left of her- watches her face multiply on screens that no one needs to look at anymore.

At some point -difuse, not pointed out- the film ceases to be real. It becomes animation, but not as artifice, but as surrender. People do not die. They dissolve in their avatars. Everything is chemical. Everything is chosen with pills. You can become whoever you want if you know where to buy it. No one has to remain who they were.

She floats. She looks for someone. Sometimes she seems to find him. Sometimes she doesn’t. Reality stretches, fragments. The animation shows everything without compromise: liquid buildings, translucent bodies, evaporating cities. It is not science fiction. It is emotional ruin drawn with fluorescent marker.

There is a question that is never asked but lingers in every scene: if all the memories are stored, if all the versions of you are out there, functioning, generating income, what is left of you when you decide to no longer participate?

Nothing is resolved. There is no climax. Only drift.

Annihilation (2018)

The first time I saw Annihilation I thought I didn’t understand anything. Then I realized that understanding was the least of it. What this film tells is not a story, but a process: of mutation, of dissolution, of slow contagion between what we thought we were and what is already something else. There is an expanding zone, the Shining, where biology is rewritten without warning. Cells do not obey. Forms duplicate, blend, open like flowers that should not exist. There is no logic. There is no message. Only strange beauty, and destruction that looks too much like creation.

The expedition is female, but the film does not make a flag of it. They are simply there, as others might be, trying to understand something that does not answer. They advance through swamps, abandoned bases, deformed forests, new ruins. Something watches them. Something copies their gestures. Listens to them. It reproduces them. As if the environment learns and returns degraded or perfected versions of itself. And the worst thing is not that they die. It is that they change. That they no longer know if what they feel is theirs or part of the ecosystem. That, in the end, their reflection is still there, moving with a different rhythm, but moving just the same.

The film does not seek an explanation. Nor a concrete emotion. It moves like a spore floating in murky water. Each scene can be read as a symbol, or as an infection. There is biological horror, but also resignation. And in the background, a very simple idea: sometimes, what destroys does not come from outside. It looks too much like us. It imitates us precisely. It improves us. It replaces us.

So I’m not sure if Annihilation should be on this list. But what I do know is that, after watching it, I spent several days thinking about how certain things – pain, love, the body – also change shape without us being able to stop them. And how, even knowing that, we keep walking towards the center.

Infiltrator (2001)

I don’t remember choosing to watch it. It was one of those movies that appeared late on TV, unannounced, unpretentious. Just a generic, almost lazy title, and a protagonist – Gary Sinise – who even then seemed like a man who had been robbed of something important. The story starts fast: a government engineer, accused of being an android infiltrated by aliens, tries to escape while trying to prove he’s still human. That’s the plot on the surface. But Infiltrator is about something else.

It is Philip K. Dick distilled in a laboratory room: the doubt about identity, the fear of the body, the suspicion that what you feel does not belong to you at all. Every time the protagonist tries to prove his humanity, he does it in desperation. Not to save his skin. To recover something he doesn’t even know if he had.

Visually, it is a modest film. It does not try to be spectacular. You can see the origin as a short project expanded to a feature film without much budget. But therein lies part of its strength. The technical limitations give it a dry texture, a world that seems to be built with recycled pieces. Everything is functional, gray, almost clinical. And that atmosphere fits. Because here there is no epic or speeches. Only flight. Only suspicion. Only the vertigo of thinking that you may have been replaced from within.

What I remember most is not the twist -which it has- nor the resolution. It’s that sequence in which he, alone, looks at his hands and is not sure what he sees. Because you can remember your childhood, you can cry for someone you’ve lost, you can feel real anguish… and still not be quite sure you are who you think you are.

Prospect (2018)

In an undated future, a father and his daughter – Cee, almost a teenager – descend on a forest planet to fulfill a mission: to extract some organic gems called “aurelacs”, valuable and dangerous to collect, as if the universe also had organs that could be removed. They arrive late, with a dirty suit and polluted air. There is no backup, no plan B. Just a poorly translated map and a biological clock that is running out.

The father acts as if everything is normal. He bargains, haggles, lies. The daughter observes. She distrusts. She is not a heroine. She doesn’t want redemption. She’s just trying to understand at what point she stopped being able to trust him.

In the midst of all this, Ezra appears. Pedro Pascal before he was Pedro Pascal. He talks in a strange, almost ritualistic way. His presence makes you uncomfortable, but you can’t help but listen to him. As if he’s speaking from an earlier version of language. You don’t know if he’s going to kill you or help you. Maybe he doesn’t know either.

This is where the film turns. At that exact point where survival ceases to be only physical and begins to involve moral decisions, precarious bonds, pacts that are not signed. There is no spectacle. No twists. No grandiloquence. But every scene has a subterranean tension. As if everything could go to hell with a single misunderstood glance.

Prospect’ s science fiction doesn’t come from its ships or its weapons. It comes from the language. From the use of terms that are dropped without explanation, as if the world were already built and you had arrived late. That gives it veracity. Body. It doesn’t need to tell you everything, because it assumes you’re smart enough to grope your way around.

And in the end, what remains is not a story about space mines, nor about hunting for valuable stones. It’s a rough tale about growing up, distrust, and learning to choose without guarantees. Prospect doesn’t impose itself. It lingers. Like a stain on the glove. Like the metallic taste of air you can’t quite breathe.

Silent Running (1972)

There are movies that arrive late everywhere and yet they are waiting for you. Silent Running is one of them. I discovered it already knowing how it ended, but that didn’t stop it from crushing me. The plot is simple: the Earth has ceased to have vegetation, the last forests survive in space domes floating near Saturn. And one of the people in charge of taking care of them, space gardener Freeman Lowell, decides not to obey the order to destroy them.

That’s all. One decision. The man who refuses to turn off the last lamp.

And from then on, silence. Silence full of internal noise. A man alone, surrounded by plants, bugs, memories. And three robots -Huey, Dewey and the one that will no longer be- that do not speak but accompany. They don’t make jokes, they don’t save the day, they don’t evolve. They are just there. As mourning companions, as emotional extension of a guy who has lost everything but guilt.

The ship is not futuristic. It’s old, it’s ugly. It has real buttons, rust on the edges. You can see the effort of having wanted to build an ark in space without knowing if it was worth it, and that doubt runs through everything. What’s the point of saving a forest if no one will see it? What’s the value of caring for something if no one wants it anymore?

Bruce Dern does something that not many actors would know how to do: to be childish, idealistic, violent, sad… all without seeming contradictory. He’s a man the world has turned its back on, and who decides to keep what the world has thrown away. That doesn’t make him a hero. It doesn’t even make him a martyr. Just someone who can’t help but love what everyone else has already forgotten.

Silent Running was filmed before the word “environmentalism” as we understand it today existed. But it is a desperate love letter to a planet that can no longer be returned to. Her songs – those Joan Baez folk ballads that sound out of place yet perfect – hurt more with age. Not because they are sad, but because they seem to sing from a place where there is no one left to listen.

After Yang (2021)

Sometimes a film comes not as a story, but as a question. After Yang asks what’s left of a person when it stops working. And it’s not even a person. It’s Yang, an android bought as a sibling for an adopted girl, a companion designed to make her feel not so lonely. An educational, kind, silent replicant. A memory with legs.

And then, one ordinary day, Yang shuts down.

The story begins when it is too late. The father – played by a Colin Farrell restrained to the point of purity – tries to repair it, like someone who takes an appliance to the workshop. But when he opens it, he discovers something he didn’t expect: an archive of memories. Fragments that Yang kept, without anyone asking him to, without it being in his program. Glances. Moments. Bodies in movement. Light filtered through leaves.

What follows is not a thriller. It is not an investigation. It is a silent mourning. The father traces Yang’s life like someone leafing through an album of someone he loved, but without knowing it. He finds clues, yes. A woman. A routine. A tenderness he failed to see while Yang was there, perfectly functional. He discovers, in passing, what he didn’t know about his daughter. About his partner. About himself.

Kogonada directs as if each shot were a meditation. There is no shouting. No pushing soundtrack. Just silences and soft colors. The future, here, has no holograms or explosions. It has trees. It has tea routines. It has technology that seems harmless because it is already integrated into everyday life. And yet, everything hurts more.

After Yang ‘s science fiction poses no great philosophical dilemmas. Just one: what does it mean to remember? And one more, hidden: can someone, even if they were fabricated, leave a real absence?

No Comments